Moritzburg Castle

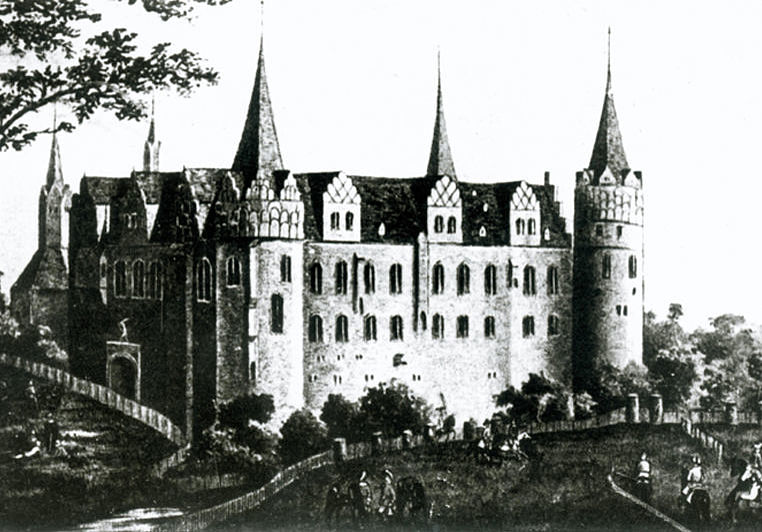

Moritzburg Castle’s modern architectural appearance is shaped by its construction and use as an archbishop's residence and its later conversion into an art museum. Essentially, the historical complex of four wings enclosing a courtyard is an impressive-looking construction dating to the transition from the late Middle Ages to the early Renaissance.

From a bishops’ residence to an art museum

The castle’s heyday came at the start of the 16th century under Cardinal Albert of Brandenburg, when it was a magnificently furnished archbishop’s residence. After its destruction in the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648), time appeared to stand still for the ruins for some 250 years.

This was not changed by the castle’s use as a barracks in the 18th century, or by Friedrich Schinkel’s ambitious plans to turn it into a university in the 19th century. It was not until 1900 that the historical ensemble was brought back to life, housing the municipal art museum of Halle an der Saale until 1917.

The castle of modernism

Today, the museum uses all four wings of Moritzburg Castle, which has boasted a modern extension to the west and north wings since 2008. The different ways in which Moritzburg Castle was put to use over its 500 years have constantly altered its appearance. Today, it is an impressive architectural monument in the centre of Halle an der Saale.

A castle, a ruin, a museum

Fascinating down to the tiniest detail: find out more about the eventful history of Moritzburg Castle’s use and construction.

Construction and use as an archbishop's residence

Moritzburg Castle in Halle is one of the most impressive late mediaeval residential complexes in central Germany. It was built in around 1500 on the northwestern fringes of the city centre, both as a splendid residence and as a fortified castle; as the seat of the Magdeburg archbishops’ regional government. It was considered the most effective defensive system of its time. The complex took its name from the patron saint of the Magdeburg archbishopric, Saint Maurice.

The foundation stone was laid by Archbishop Ernest of Saxony (1476–1513). By 1503, most of the structure was completed. Under Ernest's successor, Cardinal Albert of Brandenburg (1490–1545), it was fitted with very ostentatious decor, with precious wooden panelling, magnificent tiled stoves, sumptuous carpets, murals and valuable paintings by the great artists of the time, including Cranach, Dürer, Baldung Grien and Grünewald. The west and north wings which now hold the new museum rooms once contained the archbishop’s state apartments, plus private living and working spaces.

In 1531, Cardinal Albert began constructing a “new building” as a second residence to the south of the cathedral. This “new residence” joined Moritzburg Castle and the cathedral to form a unique ensemble of Renaissance residences that towered impressively over the Saale. In 1541, the pressure of the Reformation forced Cardinal Albert to leave the city, taking all his movable property with him.

In the years leading up to 1680, other archbishops and Protestant administrators succeeded him at Moritzburg Castle. During the Thirty Years' War, following various sieges, the castle became uninhabitable due to a fire in 1637. The original furnishings were almost completely lost.

Romantic ruin and conversion into an art museum in the time leading up to 1917

In 1680, under the provisions of the Peace of Westphalia, Moritzburg Castle fell to the Great Elector, Frederick William of Brandenburg (1620–1688). In 1717, the Prussian Old Anhalt regiment entered Halle an der Saale, led by Leopold I, Prince of Anhalt-Dessau (1676–1747). The baroque military hospital now used for the museum’s administration was built in 1777 between the gate tower and the chapel, and is a testament to that new use as a garrison.

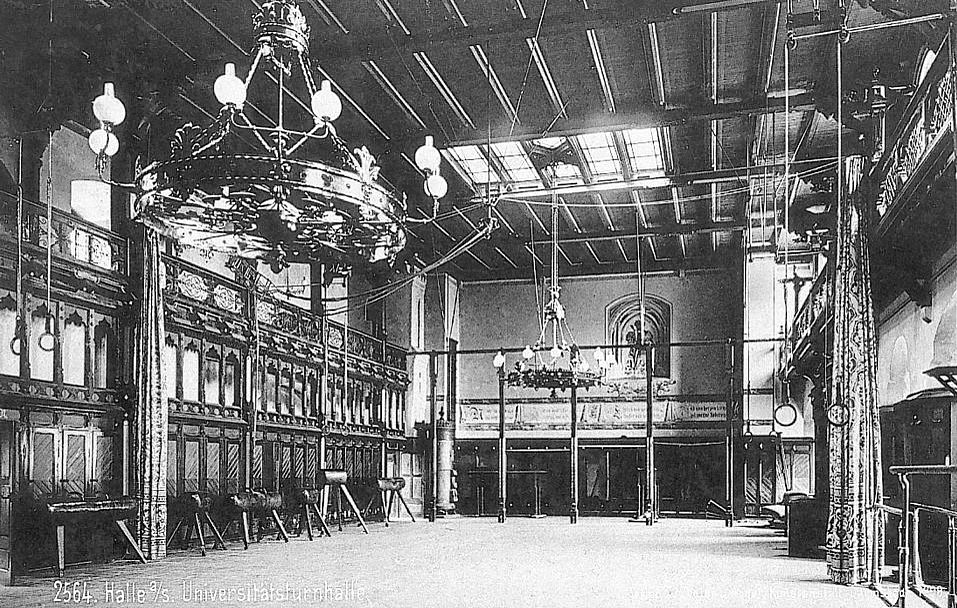

In the 19th century, Moritzburg Castle once again became a focus of attention as it fell further into a dangerous state of disrepair. In 1829, Karl Friedrich Schinkel (1781–1841) made plans, which never went through, for developing the ruins for use by the university. It was not until shortly before 1900 that the town council decided to develop the north wing, adding a gymnastics hall and fencing rooms for the Physical Education Institute at the University of Halle-Wittenberg. The university also took over the Maria Magdalena Chapel, whose fan vaulting was reconstructed in 1898.

Work started on converting Moritzburg Castle into a museum in around 1900. Some derelict working quarters were replaced by a replica of the old “Thalhaus” previously behind St. Mary's on the Hallmarkt square; torn down in 1882, this was the headquarters of the Pfänner and Halloren open-pan salt works. Its valuable fittings were preserved and fitted into the upper floor of the replica in Moritzburg Castle. This neo-Renaissance gem, still known as the Talamt, was completed in 1904. It was used to exhibit the applied art collections of the municipal Museum of Arts and Crafts, founded in 1885.

From 1911 to 1913, the battlement walk in the east wing, on the side of the town centre, was given historical stuccoed ceilings as an extension to the museum. In 1917, work was completed on the construction of a domed roof for the hall in the southeastern tower, based on the Pantheon in Rome.

Development into a modern art museum

When the Talamt building was restored at the turn of the millennium, it emerged that the historical rooms and those dating back to its construction were not suitable for presenting all groups of works. As there was no question of building a new museum, the obvious answer was to extend the museum by developing and converting the west wing. The last structural alteration, a hallmark of Moritzburg Castle’s current appearance, is the modern extension in the west and north wings, built between 2005 and 2008 based on plans by the two Spanish architects Fuensanta Nieto and Enrique Sobejano.

The architects’ design was based on an idea that is as simple as it is clever: the west and north wings of the late-mediaeval residence were connected by an aluminium-covered roof shaped by raised rooflights, rising and falling like an irregularly folded platform, though its flat surface never protrudes above the top of the wall. The historical architectural styles and shapes of the 15th to the 20th centuries are thus combined with a postmodernist vocabulary of form.

The entire length of the west and north wings of Moritzburg Castle were retained inside the old building fabric in the shape of large structural forms. The upper floors of the exhibition rooms are suspended from the roof as white cubes, and can be reached via a gallery extending along the outer walls. In the west wing, the stones of the castle’s outer walls have been left visible as the historical building envelope, evoking memories of the old ruins. The architectural devices of postmodernism remain independent and enter into a fascinating dialogue with the historic building.

By this means, the place and its colourful history have successfully been artistically brought into the present. Moritzburg Castle’s present architectural appearance thus also stands for the museum’s new beginnings at the start of the 21st century.